Processes 101

Processes are the programs that are running on your machine. They are managed by the kernel, where each process will have an ID associated with it, also known as its PID. The PID increments for the order In which the process starts. I.e. the 60th process will have a PID of 60.

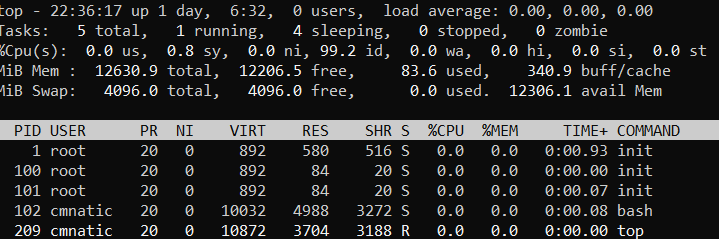

Viewing Processes

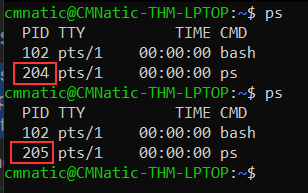

We can use the friendly ps command to provide a list of the running processes as our user's session and some additional information such as its status code, the session that is running it, how much usage time of the CPU it is using, and the name of the actual program or command that is being executed:

Note how in the screenshot above, the second process ps has a PID of 204, and then in the command below it, this is then incremented to 205.

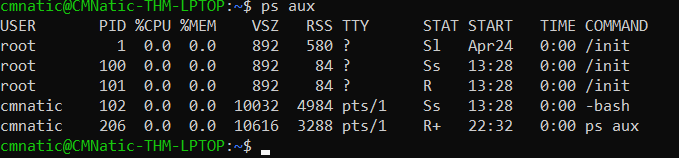

To see the processes run by other users and those that don't run from a session (i.e. system processes), we need to provide aux to the ps command like so: ps aux

Note we can see a total of 5 processes -- note how we now have "root" and "cmnatic"

Another very useful command is the top command; top gives you real-time statistics about the processes running on your system instead of a one-time view. These statistics will refresh every 10 seconds, but will also refresh when you use the arrow keys to browse the various rows. Another great command to gain insight into your system is via the top command

Managing Processes

You can send signals that terminate processes; there are a variety of types of signals that correlate to exactly how "cleanly" the process is dealt with by the kernel. To kill a command, we can use the appropriately named kill command and the associated PID that we wish to kill. i.e., to kill PID 1337, we'd use kill 1337.

Below are some of the signals that we can send to a process when it is killed:

- SIGTERM - Kill the process, but allow it to do some cleanup tasks beforehand

- SIGKILL - Kill the process - doesn't do any cleanup after the fact

- SIGSTOP - Stop/suspend a process

How do Processes Start?

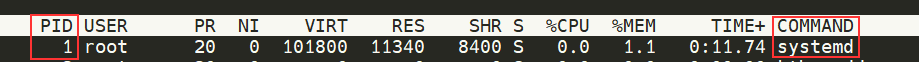

Let's start off by talking about namespaces. The Operating System (OS) uses namespaces to ultimately split up the resources available on the computer to (such as CPU, RAM and priority) processes. Think of it as splitting your computer up into slices -- similar to a cake. Processes within that slice will have access to a certain amount of computing power, however, it will be a small portion of what is actually available to every process overall.

Namespaces are great for security as it is a way of isolating processes from another -- only those that are in the same namespace will be able to see each other.

We previously talked about how PID works, and this is where it comes into play. The process with an ID of 0 is a process that is started when the system boots. This process is the system's init on Ubuntu, such as systemd, which is used to provide a way of managing a user's processes and sits in between the operating system and the user.

For example, once a system boots and it initialises, systemd is one of the first processes that are started. Any program or piece of software that we want to start will start as what's known as a child process of systemd. This means that it is controlled by systemd, but will run as its own process (although sharing the resources from systemd) to make it easier for us to identify and the likes.

Getting Processes/Services to Start on Boot

Some applications can be started on the boot of the system that we own. For example, web servers, database servers or file transfer servers. This software is often critical and is often told to start during the boot-up of the system by administrators.

In this example, we're going to be telling the apache web server to be starting apache manually and then telling the system to launch apache2 on boot.

Enter the use of systemctl -- this command allows us to interact with the systemd process/daemon. Continuing on with our example, systemctl is an easy to use command that takes the following formatting: systemctl [option] [service]

For example, to tell apache to start up, we'll use systemctl start apache2. Seems simple enough, right? Same with if we wanted to stop apache, we'd just replace the [option] with stop (instead of start like we provided)

We can do four options with systemctl:

- Start

- Stop

- Enable

- Disable

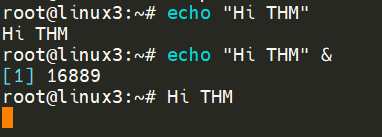

An Introduction to Backgrounding and Foregrounding in Linux

Processes can run in two states: In the background and in the foreground. For example, commands that you run in your terminal such as "echo" or things of that sort will run in the foreground of your terminal as it is the only command provided that hasn't been told to run in the background. "Echo" is a great example as the output of echo will return to you in the foreground, but wouldn't in the background - take the screenshot below, for example.

Here we're running echo "Hi THM" , where we expect the output to be returned to us like it is at the start. But after adding the & operator to the command, we're instead just given the ID of the echo process rather than the actual output -- as it is running in the background.

This is great for commands such as copying files because it means that we can run the command in the background and continue on with whatever further commands we wish to execute (without having to wait for the file copy to finish first)

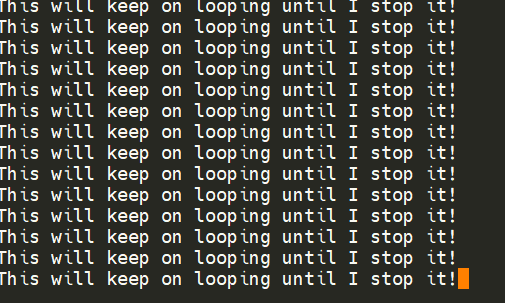

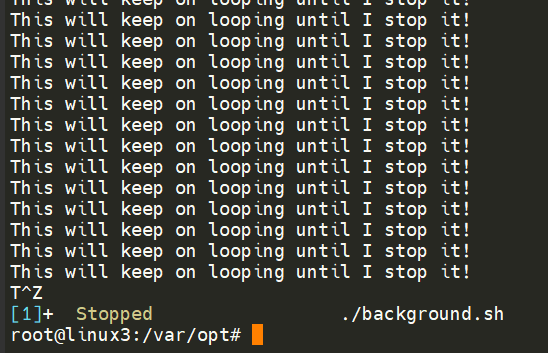

We can do the exact same when executing things like scripts -- rather than relying on the & operator, we can use Ctrl + Z on our keyboard to background a process. It is also an effective way of "pausing" the execution of a script or command like in the example below:

This script will keep on repeating "This will keep on looping until I stop!" until I stop or suspend the process. By using Ctrl + Z (as indicated by T^Z). Now our terminal is no longer filled up with messages -- until we foreground it, which we will discuss below.

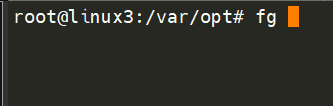

Foregrounding a process

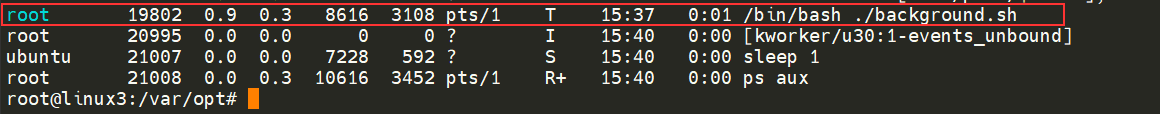

Now that we have a process running in the background, for example, our script "background.sh" which can be confirmed by using the ps aux command, we can back-pedal and bring this process back to the foreground to interact with.

With our process backgrounded using either Ctrl + Z or the & operator, we can use fg to bring this back to focus like below, where we can see the fg command is being used to bring the background process back into use on the terminal, where the output of the script is now returned to us.